THE BACTERIOPHAGE IN THE ORGANISM.

Note by R. Appelmans, presented by R. Bruynoghe.

Methods:

The article was scanned and OCRed using French as the recognition language. The OCRed text was then corrected as needed (as shown in gray). The corrected text was then translated by Claude.ai, which prior to that point was not involved in the effort. Claude.ai was then asked to generate an abstract-style narrative summary (which was then corrected manually as appropriate) and then an assessment of precedence that might be claimed by the work.

Summary by Claude.ai:

This research by R. Appelmans investigated the fate of bacteriophage in animal organisms as part of studies on its therapeutic value. Using guinea pigs and mice, the authors examined bacteriophage behavior following both oral and injectable administration, employing a functional detection method in which organ samples or excreta were added to broth, heated to 56°C to inactivate bacteria while preserving phage, then inoculated with susceptible microbes to detect growth inhibition.

When bacteriophage mixed with bread was given orally to animals, the bacteriophages appeared regularly in feces for several days, persisting longer when susceptible gut microbes were present for it to parasitize. The phage’s resistance to acids and enzymes explained its survival through the digestive tract. However, examination of internal organs revealed no bacteriophage penetration across the intestinal mucosa, a finding the authors attributed to the principle’s inability to dialyze, suggesting it could not pass through biological membranes.

In contrast, injected bacteriophage rapidly entered the bloodstream in accordance with earlier findings by Bordet and Ciuca. However, its presence in blood was brief, as it was progressively eliminated through the kidneys and intestines, disappearing completely within 24 to 48 hours depending on dose, with no traces detected after five days. Notably, the spleen retained substantial quantities of bacteriophage even when it had been cleared from other organs, a phenomenon the authors connected to the spleen’s known role in retaining microbes during infections. This splenic persistence was temporary; after fifteen days, no bacteriophage remained, which the authors attributed to neutralization by antibacteriophage antibodies that form in the organism, as demonstrated by Bordet, Ciuca, and Maisin. The authors emphasized that the bacteriophage detected in organs was not produced by organ-induced bacterial modification as Bordet’s theory might suggest, since control experiments with normal organs or organs from bacteriophage-fed animals never yielded bacteriophage in cultures of susceptible bacteria.

Translation by Claude.ai:

Our research on the therapeutic value of bacteriophage has led us to examine the question of its fate in the organism.

We first investigated whether the bacteriophage supplied to the animal by the digestive route is absorbed. For this purpose, we give guinea pigs and mice the lytic filtrate in question, mixed with bread, and we examine the feces and organs of these animals.

The feces are added to broth, supplemented with a crystal of thymol. After 24 hours we take an ampoule of it, which we heat to 56° for one hour. We place two drops of the contents of this ampoule in a tube of broth, which we inoculate with the receptive microbe.

(Note from claude.ai: “’Réceptif’ (receptive) refers to a bacterial strain susceptible to the particular phage being tested, which is standard terminology for this period.”)

We observe that there is inhibition of growth in these tubes; which we attribute to the presence of bacteriophage and not to the trace of thymol. Indeed, if we heat the contents of this tube to 56° for one hour, to transfer a few drops into a new tube of broth, growth is still absent. According to our research, the bacteriophage principle is regularly found in the feces for several days; it remains there for a longer or shorter time depending on whether or not it finds microbes that it can influence (parasitize). This persistence, moreover, is perfectly explained when one takes into account its resistance to acids and to enzymes, which makes its destruction by digestive juices impossible. (1)

To search for the presence of bacteriophage in the organs, we sacrifice the animals and we aseptically remove the various organs, which we introduce into tubes of broth. If they remain sterile for 24 hours, we inoculate their contents with the receptive microbe, whose growth we monitor. In these media we detect no trace of bacteriophage. The result also remains negative when we add a few drops of the contents of the preceding tubes, heated to 56° for one hour, to broth. The bacteriophage principle therefore does not cross the intestinal mucosa; this fact is perhaps to be related to its inability to dialyze. (2)

As for the bacteriophage injected into animals, here is how we proceeded to determine its fate.

We inject variable doses of it into animals, which we sacrifice after a longer or shorter time, in order to remove the organs and to search in them for the presence of the lytic principle following the technique described above.

From the first hours following these injections, the bacteriophage is absorbed to pass into the blood, in accordance with the data of Bordet and Ciuca (3). However, its stay there is hardly long, for it is progressively eliminated from the organism, by the kidneys and the intestine, to the point of disappearing completely after 24 to 48 hours. The duration of stay varies somewhat with the inoculated dose, but after five days we have never found any trace of it. At this moment however, the spleen still contains notable quantities of it, as can be seen in the table below. This fact is to be related, it seems to us, to the role that this organ plays in infections, where…

(1) Depoorter and Maisin. Archives internationales de Pharmacodynamie et Thérapie, vol. XXV, fasc. V, VI.

(2) C. R. de la Soc. de biol., 26 January 1921.

(3) C. R. de la Soc. de biol., 29 January 1921

…it also intervenes actively to retain the microbes. In the spleen, however, the bacteriophage does not persist, given that fifteen days later, it is completely devoid of it. At this moment, the disappearance results, in our opinion, from the neutralization brought about by the antibacteriophage that forms in the organism, as shown by the experiments of Bordet, Ciuca and Maisin.

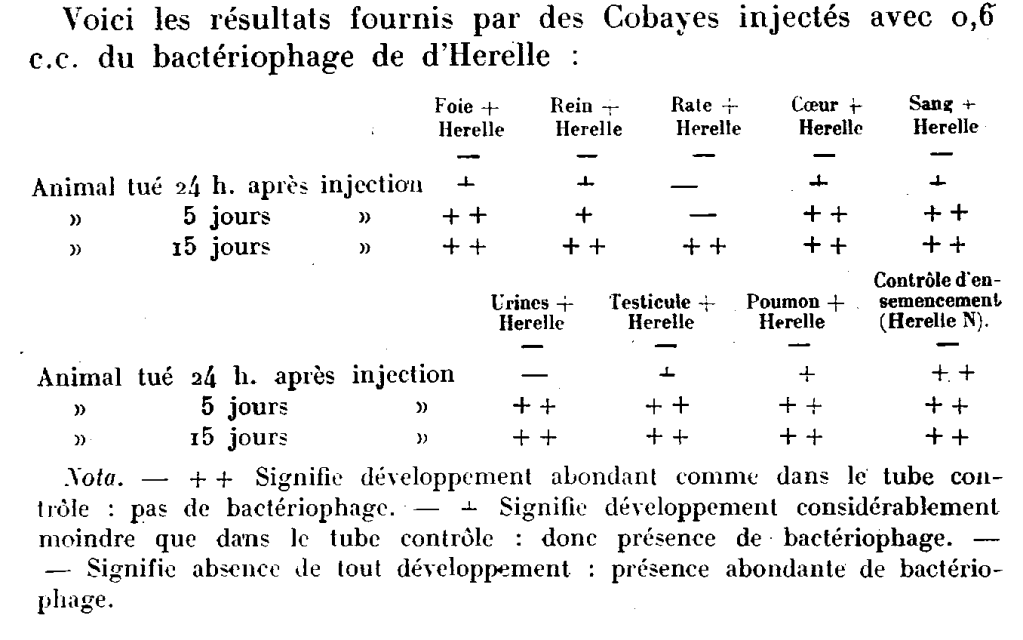

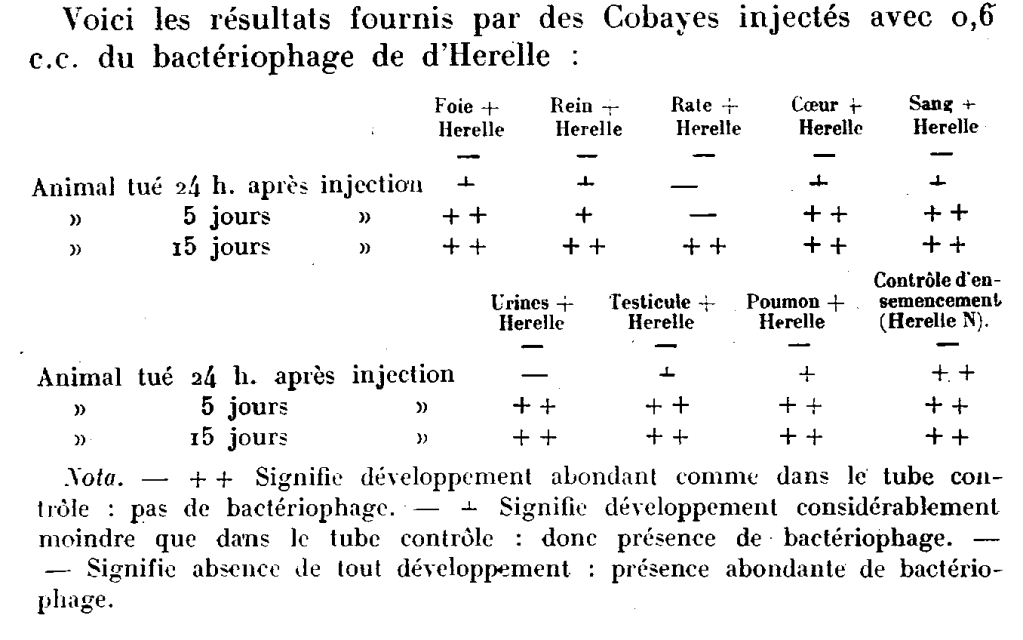

Here are the results provided by guinea pigs injected with 0.6 c.c. of d’Herelle’s bacteriophage: [see table image below]

[Table words:] Liver (Foie), Kidney (Rein), Spleen (Rate), Heart (Coeur), Blood (Sang), killed (tué), Urine (Urines), Testicle (Testicule), Lung (Poumon), Inoculation control (Contrôle d’ensemencement).

[Table footnote:] Note. – + + Signifies abundant growth as in the control tube: no bacteriophage. – + Signifies considerably less growth than in the control tube: therefore presence of bacteriophage. – Signifies absence of all growth: abundant presence of bacteriophage.

We wish to point out that the bacteriophage that we thus find in the organs is not the product of a modification operated by these organs on the microbe to make it, in accordance with Bordet’s theory, capable of secreting the ferment in question; for this principle was always absent in the tubes of broth, where the microbes receptive to the bacteriophage had undergone contact with normal organs or with organs of animals fed with bacteriophage.

Conclusions: The bacteriophage is not absorbed under normal conditions by the digestive route.

When injected, it passes rapidly into the blood to be eliminated in the urine and feces.

It persists however in the spleen, until the moment when one can admit that the antibacteriophages intervene, to neutralize and destroy it there.

Possible Precedence as suggested by Claude.ai:

[Note: This assessment of precedence is based on the document itself and may not reflect comprehensive historical research.]

This article appears to be an important early systematic study of bacteriophage pharmacokinetics and biodistribution – essentially asking “what happens to phage when you put it in an animal body?” This was a critical question for the therapeutic use of bacteriophage, which was being actively explored in the early 1920s.

Several aspects suggest precedence or importance:

- Oral vs. Injectable Routes: The finding that orally administered phage does NOT cross the intestinal barrier was significant for therapeutic applications. This would have important implications for how phage therapy should be administered.

- First Detailed Tracking Study: While the authors cite Bordet and Ciuca (1921) for the observation that injected phage enters the blood, Appelmans appears to provide the first detailed tracking of phage through multiple organs over time, including the kinetics of elimination.

- Splenic Sequestration: The observation that the spleen retains phage longer than other organs was novel and connected phage behavior to the spleen’s known immunological functions.

- Antibody Neutralization: Linking the disappearance of phage from the spleen to antibacteriophage (neutralizing antibodies) helped establish that the immune system recognizes and responds to phage as foreign material.

The dates are telling: the references are from January 1921, suggesting this work was conducted very shortly after (or contemporaneously with) Bordet’s group’s initial observations. Given that Félix d’Herelle only clearly described bacteriophage in 1917, this 1921 work represents research within just a few years of phage discovery, making it part of the foundational literature on phage biology and a key early study informing phage therapy attempts.

OCR Work and Resulting Translation:

Our research on the therapeutic value of bacteriophage has led us to examine the question of its fate in the organism.

We first investigated whether the bacteriophage supplied to the animal by the digestive route is absorbed. For this purpose, we give guinea pigs and mice the lytic filtrate in question, mixed with bread, and we examine the feces and organs of these animals.

The feces are added to broth, supplemented with a crystal of thymol. After 24 hours we take an ampoule of it, which we heat to 56° for one hour. We place two drops of the contents of this ampoule in a tube of broth, which we inoculate with the receptive microbe.

(Note from claude.ai: “’Réceptif’ (receptive) refers to a bacterial strain susceptible to the particular phage being tested, which is standard terminology for this period.”)

LE BACTÉRIOPHAGE DANS L’ORGANISME.

Note de R. Appelmans, présentée par R. Bruynoghe.

Nos recherches sur la valeur thérapeutique du bacteriophage nous ont amené à examiner la question de son sort dans l’organisme.

Nous avons recherché d’abord si le bactériophage fourni à l’animal par voie digestive se résorbe. A cet effet, nous donnons à des Cobayes et des Souris, le filtrate lytique en question, mélangé à du pain et nous examinons les selles et les organes de ces animaux.

Les selles sont ajoutées à du bouillon, additionné d’un cristal de thymol. Après 24 heures nous en prélevons une ampoule, que nous chauffons à 56° pendant une heure. Nous mettons deux goutttes du contenu de cette ampoule dans un tube de bouillon, que nous ensemençons avec le microbe réceptif.

We observe that there is inhibition of growth in these tubes; which we attribute to the presence of bacteriophage and not to the trace of thymol. Indeed, if we heat the contents of this tube to 56° for one hour, to transfer a few drops into a new tube of broth, growth is still absent. According to our research, the bacteriophage principle is regularly found in the feces for several days; it remains there for a longer or shorter time depending on whether or not it finds microbes that it can influence (parasitize). This persistence, moreover, is perfectly explained when one takes into account its resistance to acids and to enzymes, which makes its destruction by digestive juices impossible. (1)

Nous constatons qu’il y a inhibition du développement dans ces tubes ; ce que nous attribuons à la presence de bacteriophage et non à la trace de thymol. En effet, si nous chauffons le contenu de ce tube à 56° pendant une heure, pour en porter quelques gouttes dans un nouveau tube de bouillon, le développement y fait encore défaut. D’après nos recherches le principe bactériophage se retrouve régulièrement dans les selles durant quelques jours ; il y reste plus ou moins longtemps suivant qu’il y trouve ou non des microbes qu’il peut influencer (parasiter). Cette persistance d’ailleurs s’explique parfaitement, quand on tient compte de sa résistance aux acides et aux ferments, qui rend sa destruction par les sucs digestifs impossible. (2)

To search for the presence of bacteriophage in the organs, we sacrifice the animals and we aseptically remove the various organs, which we introduce into tubes of broth. If they remain sterile for 24 hours, we inoculate their contents with the receptive microbe, whose growth we monitor. In these media we detect no trace of bacteriophage. The result also remains negative when we add a few drops of the contents of the preceding tubes, heated to 56° for one hour, to broth. The bacteriophage principle therefore does not cross the intestinal mucosa; this fact is perhaps to be related to its inability to dialyze. (2)

(Note from claude.ai: “The reference to dialysis at the end refers to the inability of bacteriophage particles to pass through dialysis membranes, which was an important observation about their physical properties in early phage research.”)

Pour rechercher la présence du bactériophage dans les organes, nous sacrifions les animaux et nous prélevons aseptiquement les divers organes, que nous introduisons dans les tubes de bouillon. S’ils restent stériles pendant 24 heures, nous ensemençons leur contenu avec le microbe réceptif, dont nous surveillons le développement. Dans ces milieux nous ne décelons pas trace de bactériophage. Le résultat reste également négatif, quand nous ajoutons quelques gouttes du contenu des tubes précédents, chauffés à 56° pendant une heure, à du bouillon. Le principe bactériophage ne franchit donc pas la muqueuse intestinale ; ce fait est peut-être à rapprocher de son inaptitude à la dialyse. (2)

As for the bacteriophage injected into animals, here is how we proceeded to determine its fate.

Quant aux bactériophage injecté aux animaux, voici comment nous avons procédé pour en déterminer le sort.

We inject variable doses of it into animals, which we sacrifice after a longer or shorter time, in order to remove the organs and to search in them for the presence of the lytic principle following the technique described above.

Nous en injectons des doses variables à des animaux, que nous sacrifions après un temps plus ou moins long, afin de prélever les organes et d’y rechercher la présence du principe lytique suivant la technique exposée plus haut.

From the first hours following these injections, the bacteriophage is absorbed to pass into the blood, in accordance with the data of Bordet and Ciuca (3). However, its stay there is hardly long, for it is progressively eliminated from the organism, by the kidneys and the intestine, to the point of disappearing completely after 24 to 48 hours. The duration of stay varies somewhat with the inoculated dose, but after five days we have never found any trace of it. At this moment however, the spleen still contains notable quantities of it, as can be seen in the table below. This fact is to be related, it seems to us, to the role that this organ plays in infections, where…

(1) Depoorter and Maisin. Archives internationales de Pharmacodynamie et Thérapie, vol. XXV, fasc. V, VI.

(2) C. R. de la Soc. de biol., 26 January 1921.

(3) C. R. de la Soc. de biol., 29 January 1921

Dès les premières heures qui suivent ces injections, le bacteriophage se résorbe pour passer dans le sang, conformément aux données de Bordet et Ciuca (3). Toutefois son séjour n’y est guère long, car il s’élimine progressivement de l’organisme, par les reins et l’intestin, au point de disparaître complètement au bout de 24 à 48 heures. La durée du séjour est quelque peu variable avec la dose inoculée, mais après cinq jours nous n’en avons plus jamais trouvé trace. A ce moment toutefois, la rate en contient encore des quantités notables, ainsi qu’on peut le voir dans le tableau ci-dessous. Ce fait est à rapprocher, nous semble-t-il, du rôle que cet organe joue dans les infections, où…

(1) Depoorler el Maisin. Archives internationales de Pharmacodynamie et Thérapie, vol. XXV, fase. V, VI.

(2) C. R. de la Soc. de bioi’.,26 janvier 1921.

(3) C. R. de la Soc. de biol., 29 janvier 1921

…it also intervenes actively to retain the microbes. In the spleen, however, the bacteriophage does not persist, given that fifteen days later, it is completely devoid of it. At this moment, the disappearance results, in our opinion, from the neutralization brought about by the antibacteriophage that forms in the organism, as shown by the experiments of Bordet, Ciuca and Maisin.

…il intervient également activement pour retenir les microbes. Dans la rate le bactériophage ne persiste toutefois pas, étant donné que quinze jours après, elle en est tout à fait dépourvue. A ce moment, la disparition résulte à notre avis, de la neutralisation opérée par l’antibactériophage qui se forme dans l’organisme, ainsi qu’il résulte des expériences de Bordet, Ciuca et Maisin.

Here are the results provided by guinea pigs injected with 0.6 c.c. of d’Herelle’s bacteriophage: [see table image below]

[Table words:] Liver (Foie), Kidney (Rein), Spleen (Rate), Heart (Coeur), Blood (Sang), killed (tué), Urine (Urines), Testicle (Testicule), Lung (Poumon), Inoculation control (Contrôle d’ensemencement).

[Table footnote:] Note. – + + Signifies abundant growth as in the control tube: no bacteriophage. – + Signifies considerably less growth than in the control tube: therefore presence of bacteriophage. – Signifies absence of all growth: abundant presence of bacteriophage.

Voici les résultats fournis par des Cobayes injectés avec 0,6 c.c. du bactériophage de d’Herelle :

[These are words from the table:] Foie, Rein, Rale, Coeur, Sang, tué, Urines, Testicule, Poumon, Contrôle d’enemencement.

[This is the table’s footnote:] Nota. – + + Signifie développement abondant comme dans Ie tube Contrôle : pas de bactériophage. – + Signifie déyeloppement considérablement moindre que da’ns le tube contrôle : done présence de bactériophage. – Signifie absence de lout dévelopment : présence abondante de bactériophage.

We wish to point out that the bacteriophage that we thus find in the organs is not the product of a modification operated by these organs on the microbe to make it, in accordance with Bordet’s theory, capable of secreting the ferment in question; for this principle was always absent in the tubes of broth, where the microbes receptive to the bacteriophage had undergone contact with normal organs or with organs of animals fed with bacteriophage.

Conclusions: The bacteriophage is not absorbed under normal conditions by the digestive route.

When injected, it passes rapidly into the blood to be eliminated in the urine and feces.

It persists however in the spleen, until the moment when one can admit that the antibacteriophages intervene, to neutralize and destroy it there.

Nous tenons à faire remarquer que le bactériophage que nous trouvons ainsi dans les organes, n’est pas le produit d’une modification opérée pas ces organes sur le microbe pour le rendre, conformément à la théorie de Bordet, apte à secréter le ferment en question ; car ce principe faisait toujours défaut dans les tubes de bouillon, où les microbes réceptifs. au bacteriophage avaient subi le contact d’organes normaux ou d’organes d’animaux nourris avec du bactériophage.

Conclusions : Le bactériophage ne se résorbe pas dans les conditions normales par voie digestive.

Injecté, il passe rapidement dans le sang pour s’éliminer dans l’urine et les selles.

Il persiste toutefois dans la rate, jusqu’au moment où on peut admettre que les antibactériophages interviennent, pour l’y neutraliser et l’y détruire.